Born to a wealthy family in Yorkshire in 1330, John Wycliffe, known as “The Morning Star of the Reformation,” spent the majority of his life at Oxford University -- first as an arts and philosophy student, then as a Professor of Theology. In the 1360s, Wycliffe was Master of Balliol College, and led one of the churches at Lutterworth in Oxford. Later, he became Master of Canterbury College. Working at the University, Wycliffe wrote several works on philosophy and religion, and his lectures were an impressive commentary on the entire Bible.

When King Edward III and his son, John of Gaunt, discovered Wycliffe’s talents as a writer and debater, they drafted him to represent the King at the Bruges Conference to settle disputes between the Crown and the Roman church. Later, when Wycliffe was summoned to stand before the Archbishop at St. Paul’s Cross, John of Gaunt fiercely defended him. The trial became a shouting match between Gaunt and the Bishop of London, and ended in a riot. Following the trial, Wycliffe became severely ill, and several of the church friars came to visit him. According to historical records, they chastised Wycliffe’s beliefs and his questioning of the Church authority. Though intended to discourage Wycliffe, their words only roused him further. He arose and proclaimed Psalm 118:17, “I shall not die, but live, and declare the works of the Lord.” And with that, he was healed.

After recovery, John Wycliffe dedicated himself to the task of teaching the Bible to his countrymen, and began training a group of “poor preachers” to proclaim the Gospel throughout England. Traveling on foot to each village, they taught the Bible in simple terms that noblemen, students, farmers, and laborers could all understand. They denied church traditions and beliefs that were not based on the Scriptures, and above all, they taught the importance of the Word of God, declaring, “The Gospel is a rule sufficient of itself to rule the life of every Christian man here, without any other rule.” Wycliffe’s Latin work, De Veritate Scripturae, completed about 1378, expounded the teaching that all God's children are equal, and are all equally able to understand the Scriptures. He declared, “The Holy Scripture is the preeminent authority for every Christian, and the rule of faith and of all human perfection.”

After the publication of De Veritate Scripturae, William De Berton, Oxford Chancellor, asked a council of Catholic officials to condemn the reformer. The council determined that Wycliffe’s doctrine could no longer be taught at Oxford, and his books were burned. The next spring, a council of bishops was called to Blackfriar’s Covenant to review Wycliffe’s record. The first day of the conference, a great earthquake shook England, leading some to believe it was a Divine omen indicating that the conference should stop immediately. But the Archbishop refused to be deterred, and persuaded the council to publish a condemnation of Wycliffe’s works.

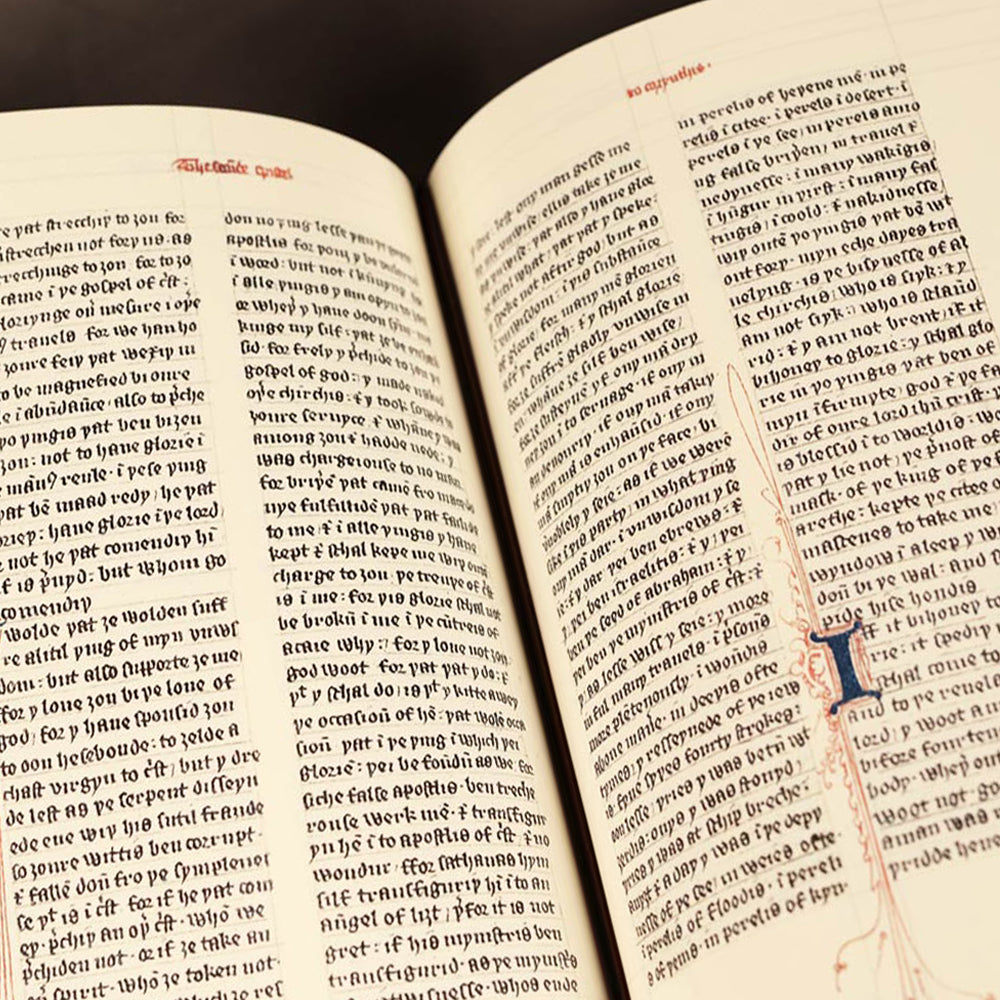

Following the council of 1382, Wycliffe returned to the church where he had ministered. Discouraged but not defeated, he resolved not only to teach the Bible, but to give people their own Bible. In their own language. Because the original Hebrew and Greek texts were not accessible, Wycliffe and his followers carefully translated the Latin Vulgate into English, word for word.

John Wycliffe died of natural causes shortly after his translation was completed, but his Bible continued to spread quickly among the common people. His followers were persecuted, tortured, and imprisoned, yet they were determined to read the Scriptures. This further infuriated the church officials, and in 1415, the Council of Constance decreed that Wycliffe’s remains be exhumed, his bones burned, and his ashes scattered across the river.